“If physical fasting is not accompanied by mental fasting it is bound to end in hypocrisy and disaster.” — M K Gandhi

Satyagraha, which means truth-force or soul-force in Sanskrit, was the core philosophy and the method of non-violent protest conceptualised, developed, and employed by Mahatma Gandhi during the Freedom Struggle Movement in India. The practice of satyagraha emphasized the power of truth and moral courage in achieving social and political change. The very essence of satyagraha was based on the principle of Ahimsa (non-violence). Gandhi believed that non-violence was not a sign of weakness but rather a powerful force that could transform individuals and societies. His ideology behind satyagraha sought to confront injustice and oppression by appealing to the conscience of the oppressor and invoking a moral awakening. Fasting was indeed a significant element of Gandhi's satyagraha. Mahatma Gandhi resorted to fasting as a matter of self-purification and to uphold the cause of truth. He fasted for different reasons to drive home the message of peace and harmony. Even during the Quit India Movement, Gandhi did not go on a fast to demand that the British should leave India. In other words, his aim behind fasting was not to settle political scores or achieve political mileage.

According to Gandhi, a hunger strike was in itself a spiritual practice of self-sacrifice. Furthermore, he considered it not just an act of ascetic self-mastery and imposition of suffering upon oneself, but also a patient education of the ‘other’, to steer them away from error and convert them by love. In Gandhi’s eyes, the sufferings of the satyagrahis would effectively demonstrate the righteousness of their cause, change public opinion, and inspire others to change themselves. However, to achieve this objective required steadfast adherence to one’s cause, courage, and a willingness to sacrifice, not to forget incredible patience. Fasting was deeply embedded in Gandhi’s everyday life, so much so that it is difficult to discern between its practice as a regime of the self from its purpose as an act of national significance. Although fasting was a key weapon employed by Gandhi during the Freedom Struggle Movement, it did not stir the conscience of many non-violent activists who were more fascinated with its strategic benefits rather than its spiritual, moral, and ethical nuances.

Between 1913 and 1948, Gandhi undertook at least 15 ‘significant’ fasts. He fasted in different places, from South Africa to various cities across India, to prisons and even at home. He fasted for innumerable causes: as penance for the immoral behaviour of his ashram inmates in South Africa; against violent protest actions of radical factions of the Independence Movement; to show solidarity with the ‘untouchables’ in opposition to the British constitutional proposal based on the separation of castes; for Hindu-Muslim unity, against communal riots; and other reasons. The duration of these fasts varied from three to four days up to even twenty-one days. In Gandhi’s eyes, fasting was a powerful tool for self-sacrifice and moral persuasion. By observing these fasts, he highlighted the sincerity and depth of his commitment to his cause. However, Gandhi’s fasts achieved mixed results. At times, he was able to secure concrete actions from other political players, such as the withdrawal of the British proposal for the separation of castes; other times he had to conclude his fast without any discernible result.

Gandhi clearly wanted to make a distinction between political hunger strikes of a routine nature and the doctrine of Satyagraha. Although he acknowledged the legitimacy of the former, he opined that the attitude of those engaged in hunger strikes had a streak of violence, with self-suffering accompanied by rancour and hostility towards the authorities, an aspect totally absent in satyagraha. According to Gandhi, while renouncing food can become one of the moral and ethical ways of showing dissent, it can also be treated as not so exemplary when it assumes an aggressive form.

In the ‘Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi’, published by the Government of India, Gandhi wrote, “The fast is not to be regarded, in any shape or form, in the nature of a hunger strike, or as designed to put any pressure upon the Government. It is to be regarded, for the satyagrahis, as the necessary discipline to fit them for civil disobedience, contemplated in their Pledge, and for all others, as some slight token of the intensity of their wounded feelings.”

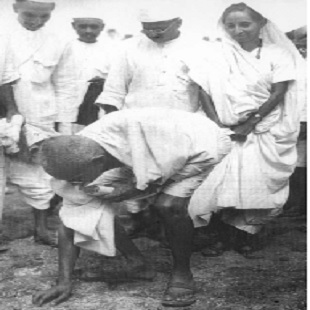

In 1925, Gandhi went on a fast in atonement for the immoral behaviour of some of the ashram occupants at the Sabarmati Ashram, along the lines of what he had undertaken at the Phoenix Ashram in South Africa way back in 1914. This fast demonstrated that his sacrifice was not undertaken for personal gain or as a form of coercion but was intended to draw attention to specific injustices and to create an atmosphere of moral urgency. By undertaking a fast, Gandhi sought to awaken the conscience of both his opponents and the general public, appealing to their sense of justice and humanity. One of the most notable instances of Gandhi using fasting as a satyagraha tactic was the famous Salt March (or Dandi March) in 1930. In protest against the British monopoly on salt production and the imposition of salt taxes, he and his followers embarked on a 240-mile march to the coastal village of Dandi, where they collected salt from the sea. Throughout the march Gandhi proclaimed his intention to fast until the British government repealed the Salt Tax. This act of non-violent civil disobedience garnered widespread attention and support, rallying the Indian masses against British rule. Whenever Gandhi fasted, and whatever the aim of his fast, he was able to establish a direct connection to thousands of people, who became his ardent followers, supporters, and fellow satyagrahis. He was uniquely able to reach their “hearts.” Gandhi’s mode of fasting was a non-instrumental act of standing for the Truth: the truth of the cause of self-rule.

A series of events, including the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, ed the launch of the Non-Cooperation Movement in 1920. This movement under the leadership of Gandhi signified a new chapter in the history of the Indian freedom struggle. It was supposed to be a peaceful and non-violent mass movement, wherein Indians were told to boycott foreign goods and adopt indigenous products; relinquish their titles and resign from government seats; not serve in the British Army; abstain from paying taxes; and refrain from attending government-run schools. However, Gandhi was forced to call off this movement when in Chauri Chaura (Uttar Pradesh), a violent mob set fire to a police station killing 22 policemen, during the violence that erupted between the police and protesters of the movement. He felt that people were not ready for a ‘passive’ revolt against the government, and Gandhi went on a fast for five days for his ‘role’ in the incident. Fasting was an integral part of his personal and political philosophy, and he used it as a potent tool within the broader framework of satyagraha.

The 1942 Quit India Movement, which aimed for India's immediate independence from British rule, was a significant moment in the Indian freedom struggle, and the fast undertaken by Gandhi played a pivotal role in mobilizing public support and intensifying the movement. During this movement, the British government arrested the prominent leaders of the Indian National Congress, including Gandhi, who was placed under house arrest in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune. Gandhi began his fast on 10th February, 1943 to protest against the arrests and demanded the release of all political prisoners. The fast was a self-imposed penance, reflecting his deep commitment to the cause of independence and his belief in non-violent resistance. The fast lasted 21 days and received widespread attention and support across India. It generated tremendous public sympathy and galvanized the masses in their resistance against British rule. As news of Gandhi's fast spread, demonstrations, strikes, and protests erupted throughout the country, leading to a significant escalation in the Quit India Movement. The British administration, fearing the potential consequences of Gandhi's deteriorating health and the growing unrest, finally succumbed to public pressure. On 18 February 1943, negotiations took place between Gandhi and the British authorities, leading to the release of political prisoners. This particular fast of Gandhi’s during the Quit India Movement symbolized his unwavering commitment to non-violence and his willingness to make personal sacrifices for the cause of Indian independence. It brought the struggle to the forefront of national and international attention and further consolidated the resolve of the Indian people in their fight against the colonists.

One of the most talked about and written about fasts Gandhi observed was in 1947 at Noakhali in present-day Bangladesh, during the partition of India. The communal violence that erupted was beyond the control of both the outgoing and incoming new government. What the army of thousands of soldiers could not achieve in Punjab, Gandhi’s fasts could achieve in Bengal. Gandhi used fasting as a tool to draw attention to the burning issue of communal violence and inspire individuals to reflect upon their actions and work towards peace and harmony. It was in January 1948 that Mahatma Gandhi sat on a fast for communal harmony – the last fast of his life. Over a span of thirty-five years (1913-1948), Gandhi had gone on fast every other year. Though the issues behind the fasts had been varied, the wisdom and nobility demonstrated by Gandhi illustrated the power of his fasting, the resilience of his mind, and his unshakeable faith in his beliefs.

Gandhi's fasts often ed public discussions and negotiations and ultimately led to concessions from his opponents. His commitment to non-violence and willingness to undertake personal sacrifices through fasting demonstrated the moral strength of his convictions and influenced public opinion. It is worth noting that Gandhi's fasts were not undertaken lightly or as a mere strategy. He approached fasting with utmost seriousness, viewing it as a spiritual discipline and a means of soul-searching. Gandhi’s fasts were an attempt to morally challenge the imperialists to engage in a process of reflection about the iniquity of colonialism. In other words, Gandhi sought to transform what may appear as a political struggle into a righteous and ethical struggle. When we analyse the history of non-violent action, Gandhi was the first to make fasting both a spiritual and political pursuit. For him, fasting was the core of moral politics and living proof of the essence of the doctrine of satyagraha. He made it a nuanced practice which can be legitimately undertaken in rare circumstances and by rare people like Gandhi himself. As for the colonists, though they attempted to downplay the significance of his fasts and occasionally responded with repressive measures, they did perceive them as a potent form of resistance.

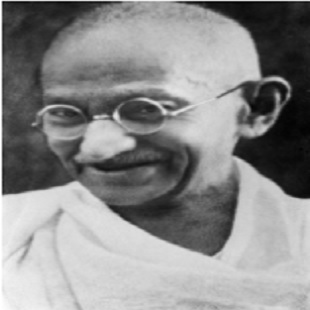

M K Gandhi

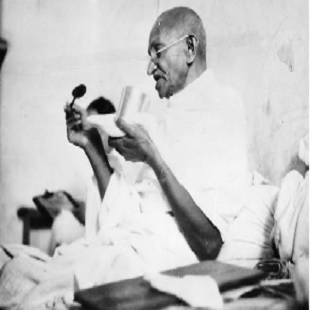

Gandhi taking his last meal before starting his fast (Rajkot Fast)

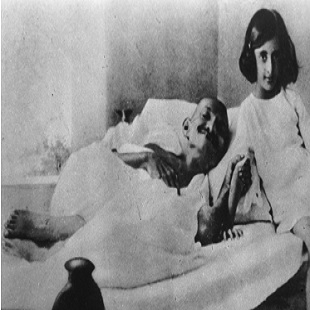

A fasting Gandhi with young Indira

The Salt Satyagraha (When Gandhi led the making of salt)

1948 – The Last Fast

Source: Indian Culture Portal